How to become an elite tutor through academic coaching

By Dr Scott R. Dempsey on 27th March, 2024

When most people think of a private tutor they think of a subject expert.

Someone who has a deep level of knowledge that they can pass down to their students in such a way that they can understand it and apply it to examinations.

And while this is important, it’s arguably not the most valuable part of what an elite tutor offers to the student.

So what is, you might ask?...

The role of Academic Coaching.

The importance of coaching in education cannot be overstated. Most students don’t have an issue with learning, they have an issue with how to learn, in the most effective and efficient ways.

Today, subject content is available everywhere; from textbooks, to websites, from bite-sized videos, to in-depth articles. The information is ubiquitous and available in every format imaginable.

So why are so many students still struggling to learn it?

Put simply, they don’t know how to learn it because they have never been taught, or coached.

In most cases, what students really struggle with is a combination of the following:

- Setting goals

- Productivity and procrastination

- Developing good habits

- Self-awareness

- Adopting the right mindset

- Managing learning differences (such as ADHD)

- Effective integration of technology

In addition to these areas we will be discussing below. Other important factors include:

- Time management

- Stress and anxiety

- Self-advocacy and independence

- Confidence and motivation

- Study skills

- Work-life balance

Coaching improves on overall performance and is a key part of so many other industries (e.g. sports, music, business, fitness and nutrition) and yet is so underutilised in education.

Here are some of the main differences between coaching and subject-tuition:

Coaching - focus is on how to learn (skill building and personal development):

- Create and work towards specific goals

- Develop a growth mindset

- Improve organisation and efficiency

- Improve time management and establish work-life balance

- Develop strategies, structures and routines

- Manage stress and anxiety

- Increase productivity

- Cultivate self-advocacy (independence)

- Improve self-awareness

- Increase self-confidence and motivation

- Improve study skills

Tutoring - focus is on learning a specific subject matter (memorising, understanding and applying information):

- Help to understand a specific subject topic

- Asks directive questions

- Provides information

- Seeks specific answers

- Based on past learning

- Requires repetition of content material

- Requires high-quality materials and resources

- Improve exam technique

An elite level tutor should be able to offer a blend of the two with an emphasis on the student as an individual. Every student will require a different approach and will be naturally stronger or weaker in specific areas. It’s the tutor’s role to figure out what coaching approach works best.

In addition to helping to develop skills such as good time management, organisation, self-advocacy and study skills, a good coach can provide motivation and accountability to the student.

In fact, studies have shown that students are more likely to have higher attendance and achieve their goals when working with a coach.

The obvious analogy is in personal training.

A personal trainer can make all the difference to your motivation and determination to reach your fitness goals. They provide additional accountability for days when you don’t feel like going to the gym, in addition to helping you to improve your technique in training, setting clear goals for progress, and personalising every aspect of the training to help you achieve those goals.

So let’s discuss some areas of academic coaching that should be implemented by an elite tutor.

Goal Setting

Goal setting is perhaps the most fundamental pillar of coaching, for good reason.

How do you know when you have reached your destination if you don’t know where you are going?

In the words of famous personal development coach, Brain Tracy “clarity accounts for 80% of success and happiness”.

Put simply, how do you hit a target you cannot see!

Goal setting can be challenging in academic settings, when students are young and often don’t know what they want to achieve, why they want to achieve it, and what the next steps are.

For GCSE and A-Level students, this can involve the following decisions:

- What subject/s do I want to specialise in?

- What university do I want to study at?

- What grades to I need to achieve to attend university?

- What subject/s do I want or need to take at A-Level?

- What GCSE grades do I need to achieve for A-Levels?

Most of these options involve some degree of long-term planning, which can be difficult without the assistance of a coach. In addition, many of these decisions can be overwhelming for the student; who might feel reluctant to select one option (in fear of removing other options), or setting clear goals for grades they want to achieve in their examinations (in case they don’t achieve them).

The problem with not setting clear long-term goals is that the student will often not know what they are working towards and their motivation will suffer. It’s always better to pick one direction and change course if necessary than working without direction in fear that they might make the wrong decision, or not achieve their goal grades.

In terms of the latter, I always suggest that students select two goal grades.

The first being the minimum grade they would be happy with (for example a student might not be happy if they achieved lower than a grade 7 in maths). The second being an aspirational grade (for example maybe with a lot of work they feel they could achieve a grade 9).

Once long-term goals have been established it’s time to break them down into smaller/shorter-term goals, which can be worked on each week.

These should be structured with a view of helping them achieve their long-term goals and will involve a lot of feedback, measurement, tracking and accountability from a coach.

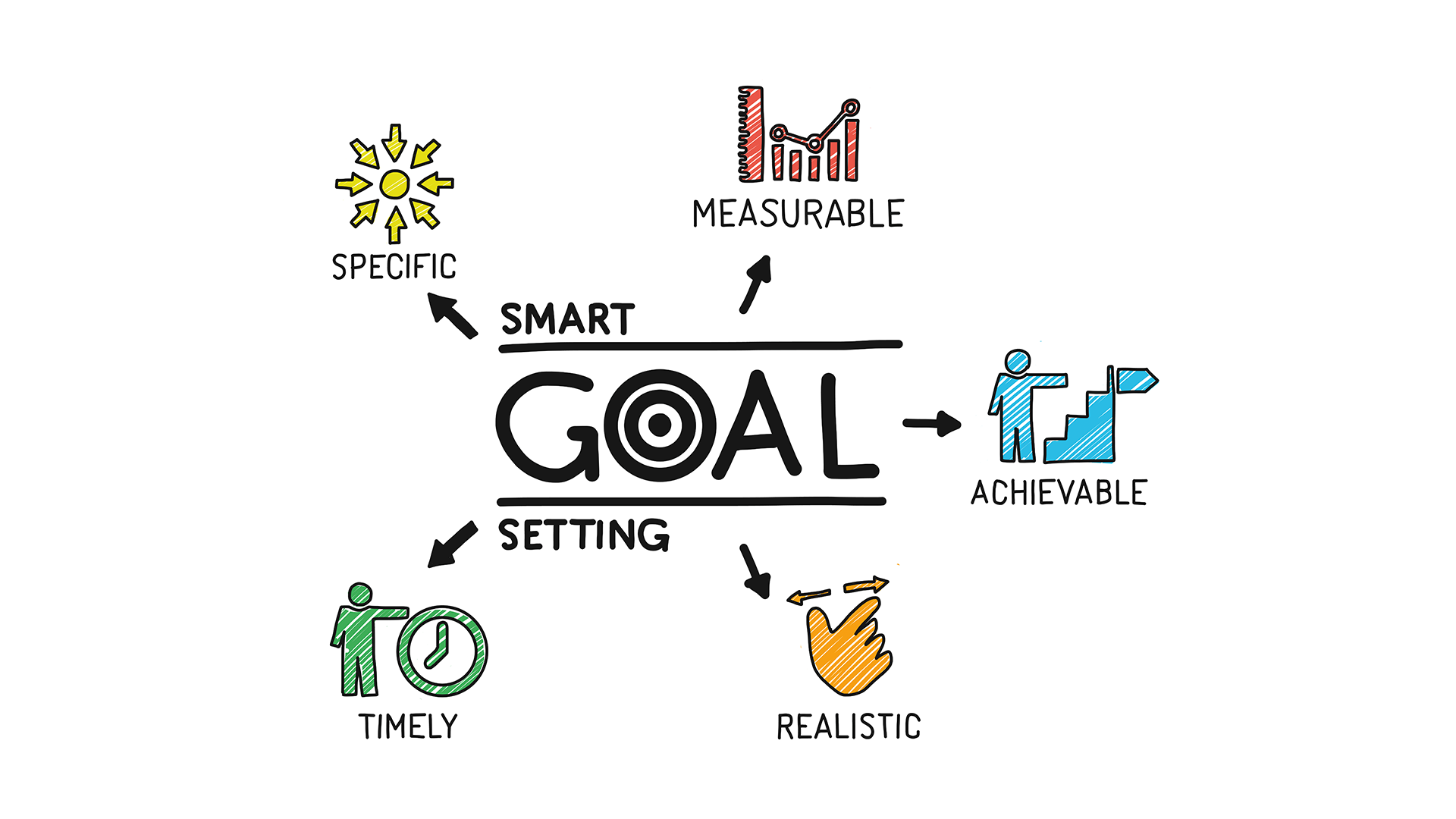

SMART goals are a great model to use for shorter-term goals. SMART stands for:

- Specific - What will you achieve this week? What will you do to achieve it?

- Measurable - What data will you use to quantify your progress?

- Achievable - Are you sure you can achieve this? What obstacles might get in the way?

- Relevant - Are your short-term goal/s aligned with your long-term goal/s?

- Time-Bound - What is the deadline for achieving your goal/s?

SMART goals are a great way for students to approach their short-term objectives.

An academic coach should be working with the student each week to ensure they are staying on track.

It’s often when students fall behind in their studies that problems arise and overwhelm and anxiety set in. By setting out a clear weekly task of objectives, a student can feel more confident and motivated, knowing that they are on the right track.

For more information on SMART goals, here is a great resource.

As a final note on goal setting, it’s important that students do not simply fill their time slots with tasks.

This is a common mistake I see them make when producing an exam revision schedule.

Simply assigning a one hour time slot to revision on chemistry, or covalent bonding, is not a measurable activity. There must be an outcome attached, which they wish to achieve, and preferably one which they can measure their progress against.

For example, completing 10 questions on covalent bonding and assessing knowledge, understanding and application gaps would be a preferred option and a goal completion would be getting a higher score than last time.

Let’s look at some other areas of academic coaching students require to become top performers.

Productivity and procrastination

Students often overestimate the amount of time they actually have for revision, particularly outside of designated revision periods.

During term time, they have a full day at school, after which they might also have clubs or other social activities. When you include homework on top and factor in one day a week off at the weekend, the amount of time available for revision is severely limited.

This makes it especially important for them to be able to maximise the time they do have, in terms of productivity, efficiency and avoiding procrastination.

An academic coach should work with the student to improve their productivity and provide them with the tools to manage procrastination effectively.

There are several ways they can do this:

- Prioritise high-value tasks

- Avoiding friction - having the right tools to hand

- Developing good habits and routines

- Use the pomodoro technique

- Reducing unnecessary distractions

The Pareto Principle states that ‘roughly 80% of outcomes come from 20% of causes’. Meaning that ~80% of the results someone achieves can often be attributed to ~20% of their actions.

This is important for students to understand, because they often feel overwhelmed with the volume of work they think is required to do well in examinations.

We can consider the 20% as high-value tasks, as opposed to the other 80%, which would be lower-value tasks; or a less productive (and effective) way to reaching their goal/s.

There are two predominant reasons for students not doing the highest-value tasks when it comes to their studies.

- They don’t know what those tasks are

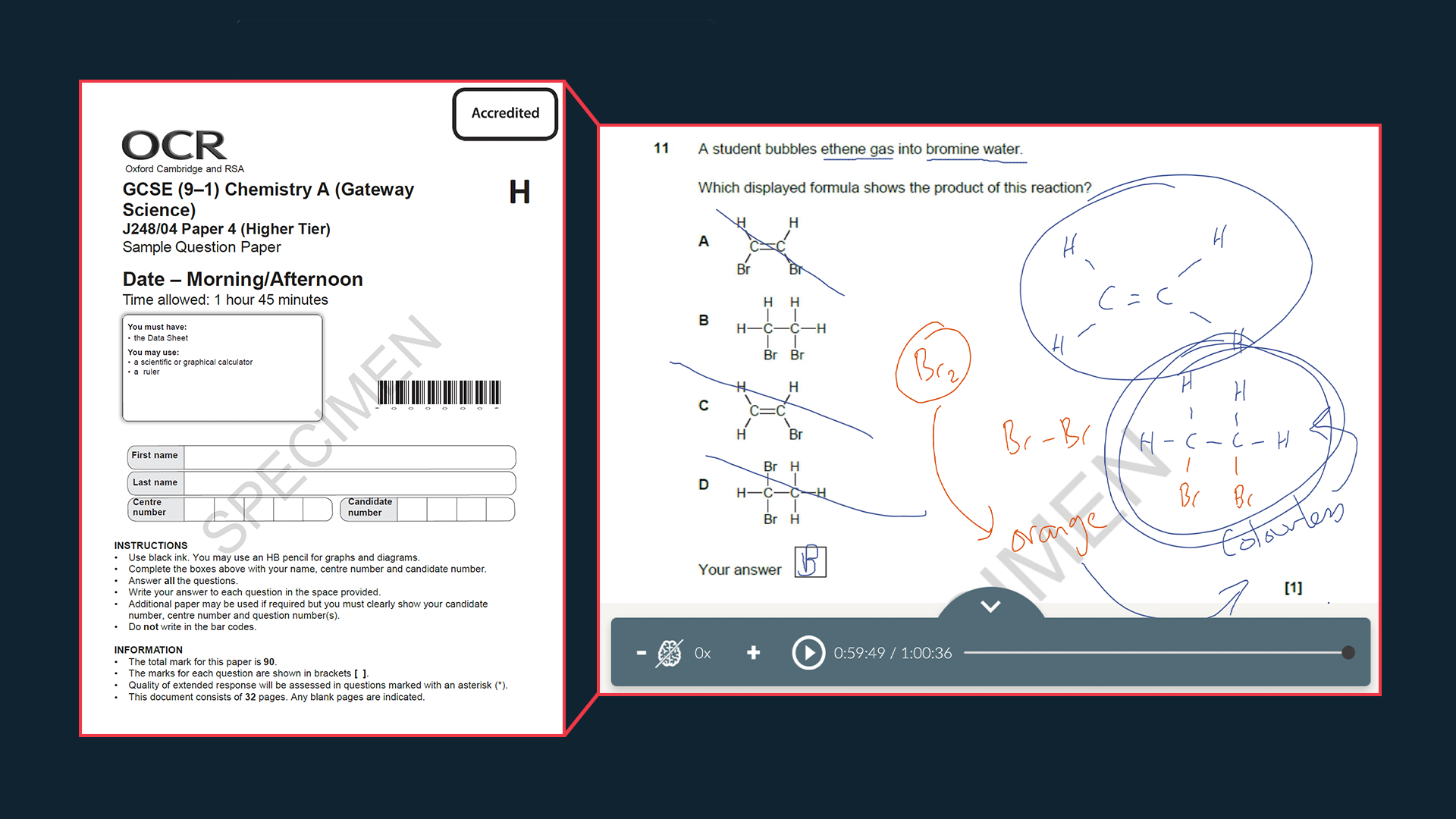

- The highest-value tasks are often those that are most difficult to do (and provide the most friction)

So what are these tasks?...

According to Elevate Education, who conducted one of the largest studies on student performance, the two top skills that predict student performance are:

Practice exams

The number one predictor of how a student would perform at school.

It may sound simple, but the majority of students spend too much time on lower-value tasks such as making notes, reading over their notes, or rewriting their notes.

A student going through a chemistry examination question with the assistance of a tutor.

While I’m certainly not suggesting they eliminate those tasks completely, they simply are less effective than practicing exams.

In fact, Elevate Education found that 76% of students (pretty close to pareto’s principle) spent most of their time memorising their notes or on memory-based activities.

An exam is not a test of memory. It does not test how you remember, it tests how you use information.

Practicing exams involves application of knowledge, which is a higher level activity than simply memorising or trying to acquire knowledge. Think about the armchair football fan, who has all of the knowledge and stats, but ask them to play against professional players and they would be out of their depth.

A well-structured timetable

Some students are naturally more organised than others. However, the importance of having a well-structured plan for revision is vital for a number of reasons.

Firstly, it removes guesswork and randomly selecting a subject/topic based on how they feel that day (which is most often be one they enjoy, or provides them the least discomfort).

Secondly, it will remove friction of starting revision, and as a result, procrastination. If the student knows exactly what they want to cover at any given time of the week, they can have their materials ready to go and spend their valuable time actually doing the task at hand.

Thirdly, linking back to the high-priority tasks, they can plan to spend the majority of their time doing the tasks which will have the greatest impact on their performance.

This is where an academic coach can really assist the student by gathering the right resources for them and ensuring that they stay on track with their timetable from week-to-week. They can also help a student to produce a well structured schedule which incorporates a good work-life balance.

We’ve discussed how to improve a student’s overall productivity. However, there is one big aspect we’ve left out…

Procrastination!

Procrastination is the destroyer of productivity. A student could have the best structured schedule in the world and be working on all the high-value tasks, but if they are constantly procrastinating, they still won’t achieve their goals.

All of us have suffered with procrastination at some point or another. This is particularly true when we perceive a task as difficult or something we don’t enjoy doing.

It makes sense, as the primitive parts of our brain are wired to keep us comfortable and avoid discomfort.

The problem is that today it’s easier than ever for students to find ways to procrastinate and focus on the latest TikTok or Instagram post.

So how can a coach assist with this?

One way is to ‘Eat the Frog First’, in the words of Mark Twain.

In other words, doing the most difficult or least enjoyable task/s first, when energy is high and will-power hasn’t been eroded away during the day. It also gives a sense of satisfaction and comfort knowing that it’s done.

An additional strategy (or one to use when doing the task first thing is not possible), is to use the Pomodoro Technique.

This technique involves breaking work into smaller, less daunting chunks. The less friction a student faces to just getting started on the task, the less likely they are to procrastinate. So this could be setting a timer for 25 minutes before taking a break, or just completing one or two questions.

It’s considerably more difficult to get started (particularly when procrastinating), than continuing when it comes to working on difficult or less enjoyable tasks. In fact, most of the time, the pain comes far more from the thought of the task than actually doing the task.

A final note on procrastination.

Once a student has gone to all the effort to get started and get into the flow of working, it’s incredibly important that it’s not broken by distractions. This includes phone calls/messages, notifications, a dog running into the room. Anything that will break their flow of concentration.

One study has shown that it can take up to 23 minutes to refocus on the task at hand once distracted. So that one Snapchat could cost the entire revision session if they are using the Pomodoro Technique. Getting into a flow state is incredibly valuable and a student needs to protect it. Especially once they have gone through the hard part to avoid procrastination and get started in the first place.

Habits

Helping a student to develop beneficial habits and routines is an integral part of academic coaching.

A habit can be defined as something that you do regularly, sometimes without knowing what you are doing (subconsciously). Or the process by which behaviour, through regular repetition, becomes automatic or habitual.

Obviously, habits can either work for you or against you, and the longer you have been engaging in a certain habit or routine, the harder it is to break.

In the words of Samuel Johnson, “the chains of habit are too weak to be felt until they are too strong to be broken.”

A student can understand and implement everything we’ve discussed above, have clarity over their goals, techniques for being productive and avoid procrastination. However, if they also have poor sleep hygiene, live on a diet of junk food, don’t exercise, and are addicted to social media, it still makes high performance and goal attainment an uphill battle.

Furthermore, one bad habit can often lead to the next…

For example, let’s say a student regularly stays up on social media and gets 3 hours of sleep. They are far more likely to try and overcome their tiredness and lethargy the next day by consuming highly caffeinated drinks all day; which thus affects the next night’s sleep.

Typically, developing a new habit, or breaking an old habit, takes over two months on average before the new behaviour becomes automatic.

As a coach you might spot that your student has several habits or routines that are not supporting their long-term goals. Here are a few tips to assist with them:

- Get the student to recognise and acknowledge their destructive habits

- The student must be willing to change their habit/s

- Only change one habit at a time

- Replace disempowering habits with empowering habits

- Work on changing habits at the right time (i.e. not in the middle of exams)

- Some students will react better to gradual changes rather than overnight changes

- Tackle habits in order of importance (effect on performance)

- Figure out the root cause of the habit

While some habits and routines are generally beneficial for all students, others need to be more personalised to the individual.

For example, some students might find that they are more alert in the evenings, while others are more alert in the morning. So structuring revision (on non-school days) will work differently depending on when the student has the most energy and focus.

Other examples include:

Nutrition

Some students might be more sensitive to certain foods, or more carbohydrate sensitive than others. So, while some students may get additional energy from a high-carbohydrate meal; others may find that it gives them brain-fog and lethargy.

In addition, some students might find it beneficial to eat several smaller meals throughout the day, while others prefer larger meals which slowly release energy throughout the day.

Of course, some of this will depend on the activity level of the student and their metabolism.

Caffeine

Caffeine is a stimulant that can help to increase alertness and concentration. However, it can also cause overstimulation and anxiety if overused or abused. Some students will be more sensitive to the effects of caffeine than others. For some, it might be beneficial, whereas for others it might cause too much stimulation.

Caffeinated drinks should be used in moderation.

In recent years highly caffeinated drinks have grown in popularity.

Shops now have sections of energy drinks almost as large as other soft drinks. Many of these drinks contain caffeine in excess of 200mg (two-to-three times the amount of a standard cup of coffee). Caffeine is also in other soft drinks, such Coca Cola and foods such as chocolate.

So it’s worth checking how much caffeine a student is consuming; particularly if they are having large energy fluctuations, problems with concentration, or struggling to sleep at night. Ideally, make a cut-off for caffeine consumption in the early afternoon as the half-life of caffeine is ~6 hours.

Exercise

Exercise is beneficial for all students, as it promotes good circulation and blood-flow to the brain. It also releases endorphins which will help to combat stress and fatigue, generally putting the student in a good state for studying.

The exercise choice is individual to the student. This can be based on preference or other factors, such as body type. Some students may prefer strength-based exercises, while others prefer endurance-based exercises. Other students may not particularly like sports, so might prefer to go for walks.

What really matters is that the student is not sedentary for long periods of time during the day, which is sometimes challenging if they feel like they need to study throughout the day.

Meditation

For the purpose of this, I consider meditation to be anything that involves calming the mind and reducing anxiety.

Again, the reason that this is so individually-based is because some students will be naturally more anxious than others. A very laid-back, calm individual might not need meditation in the way that a highly-stressed and anxious student does.

Our brain is far more receptive to receiving information and learning new things in a calm, low-brainwave state. So it is very important for the student to try and study with a clear and relaxed mind.

Touching on a previous point. If the student is someone who typically suffers from stress and performance anxiety, it might be worth eliminating additional external stimulating factors, such as caffeine, completely.

Some anxiety is not always a bad thing though.

Often those students who are more sensitive to stress are also the most driven, so it’s a bit of a balancing act. The laid-back student, who doesn’t appear to get stressed by anything often requires more stimulation to get them to put the work in.

Again. It’s all very individual. Which brings us nicely to our next topic…

Self-awareness

One key area for an academic coach to work on is developing a strong self-awareness among their students.

Self-awareness is the ability to look inward into one’s own personality or individuality.

Studies have shown that self-identity starts in adolescence and continues into early adulthood as the brain continues to develop. So depending on the age of the student, this part of coaching may be more or less applicable.

Also, there is still conflicting evidence as to whether certain personality traits are fixed from childhood, or that an individual’s personality changes gradually over time and may be subject to greater rates of change in adolescence.

Personally, anecdotal experience from myself, my brother, and school friends I’ve had since primary school, suggest that stronger core personality traits seem to persist over time.

For example, I’ve always been strongly introverted, conscientious (to the point of perfectionism) and sensitive. My brother, on the other hand, has always been highly extroverted, spontaneous and far less sensitive. This has been the case for 40 years and has dictated the skills we have today and the career choices we’ve made (in other words what we are good at).

So why is this important for a student?

Let’s look at it this way.

We can all develop skills. In any area we wish. We just can’t develop them at the same rate or to the same level. Those depend on individual (mostly genetic) preferences and personality factors. People’s brains are mechanically very similar, but very different in the way they operate.

Let’s look at Usain Bolt as an example.

I think we can all agree that he had an incredibly natural (physical) gift for sprinting. Tall with an incredible leg turnover speed. But was this what made him a champion?

Only partially.

What is often overlooked is how incredibly calm he was able to stay under extreme pressure, often seen laughing and joking around prior to major finals. In other words, he has a naturally calm demeanor.

Now take the same Usain Bolt and replace his mind with someone who has a natural propensity to suffer with chronic stress and performance anxiety. Would he still be the champion? I would argue not.

Other sprinters who don’t have that natural calm and confident personality have since tried to imitate Usain Bolt and it comes across disingenuous and might even be putting them at a disadvantage by not playing to their own strengths.

This is the true value of self-awareness. It helps us as individuals to understand ourselves better and play to our strengths (and even manage things that are not so natural to us).

Now, for the elephant in the room...

There’s no doubt that the current education system (particularly at secondary level), suits some students' personality traits and natural skillsets more than others. Much like all forms of work do.

We can’t get away from that. Unless the system changes.

Does that then mean that all students who don’t have a particular set of personality traits and skills are doomed to fail?

Absolutely not.

That’s where the role of an academic coach comes into play. To identify strengths, weaknesses and proclivities at an early stage and put the student in a situation where, as much as possible, they are using their strengths and getting assistance with their weaker areas.

Let me share my own personal experience of this.

At school I was naturally good at art and sports. Yet I ended up with a PhD in Science.

How did that happen?

Well, through self-awareness I realised that my strengths were not using pure logic (as maths and science) often require. Instead, I was able to adapt my learning to include more creative, visual and kinesthetic techniques.

This will often involve some experimentation and not necessarily using the techniques that were passed down to you from a teacher - who might be a very different type of learner.

I was able to use my introverted nature and conscientiousness to spend long periods of time studying alone. However, my sensitive and anxious nature meant that I needed to manage stressful situations, such as exams, with a lot of self-care and consideration for external stimulating triggers.

None of this would have been possible without some degree of self-awareness.

So where do you start as a coach?

While a more comprehensive discussion on the use of psychometrics is for a separate article, here are some good resources to start:

Personality Tests

Career Test

The Holland Code (RIASEC) Test

Psychometric tests are a useful tool for a coach.

However, it’s important to note that they do not define someone. They simply highlight what an individual’s preference might be. The higher the percentage, the more strongly the individual is likely to display that particular trait.

It’s also important to remember that these tests are typically designed for adults and students might require a little assistance with the context of the questioning. I’d also consider doing some training courses on psychometric test analyses before attempting to interpret and relay the results to your students.

As a final note. I would probably avoid using these self-assessment tests with students younger than 14. While they might be fun for younger students, it will rely strongly on the coach to monitor the skills and personality preferences for certain age groups.

Mindset

“Whether you think you can or think you can’t, you’re right” - Henry Ford

It goes without saying that the mindset a student adopts towards their studies will dictate how successful they ultimately are in achieving their goals.

Renowned personal performance coach, Tony Robbins suggests that mindset is the most crucial component in high achievement. In fact he hypotheses that ~80% of success is psychological and only ~20% mechanics (there’s that 80/20 rule again!).

Tony categorsies a personal breakthrough into 3 key areas, the first 2 of which are based on mindset:

- Your State

- Your Story

- Your Strategy

Let's take a look at each one in a little more detail...

Your State

In order of importance, your state of mind is top for good reason.

If you are in a lousy state, angry, or miserable when aiming to achieve or complete something, your brain will not be very receptive to it. You’ll feel low in energy and mood and everything will feel like an uphill battle. Clearly, this is not a recipe for effective study.

It's a coaches job to ensure that a student is in a peak state to study as often as possible.

If a student is feeling in a lousy state prior to every study session, the coach must identify it and use tools to change it.

These tools can be any of the following:

- Exercise

- Meditation

- Venting - getting things off thier chest

- Cold showers or drinking cold water

- Music

- Humour

These tools mostly involve changing the students physiology; which will in-turn, change their mindset to a more positive state.

Your Story

Your story refers to your inner dialogue and beliefs. What ‘story’ you are telling yourself.

A student who tells themselves that they can do or achieve something is very different to a student who is constantly telling themselves they can’t.

The number of times I’ve heard students tell me that “I’m just not good at maths”, or that “maths is not my strong suit.” They are immediately setting themselves up to fail through their story.

Furthmore, what a student believes becomes reinforcing.

So let’s say they tell themselves that they are not good at maths, they start to enjoy it less, they avoid it more, and their brain is less receptive to learning it. In some cases they might even start to fear it. This will obviously result in a poor test score next time and the cycle continues.

Of course, the same is also true for positive reinforcement. Which is the academic coach’s job to try and install.

Your Strategy

Finding the right strategy is often the easiest thing to change.

For a student, this could be the type of resources that work best, or putting together a well-structured timetable for revision. A strategy is simply an effective plan of action.

However, if a student’s state and the story are not addressed first, a good strategy will only go so far.

For example, picture two students, both with the same strategy (a revision plan that works well for both).

Student one is constantly in a lousy state, fed up that they have to do more revision and looking forward to finishing. They tell themselves that they hate maths and have never been any good at it.

Student two, on the other hand, is happy and energised, looking forward to progressing in the topic they have planned as it’s a step towards achieving their goal. They believe that as long as they put the work in they can get good at anything they put their mind to.

Which one is likely to do better at the end of the year?

Carol Dweck is Professor of Psychology and a best selling author for her book ‘Mindset. Changing the way your think to fulfil your potential’.

Carol spent her career studying students' attitudes and beliefs about failure and success.

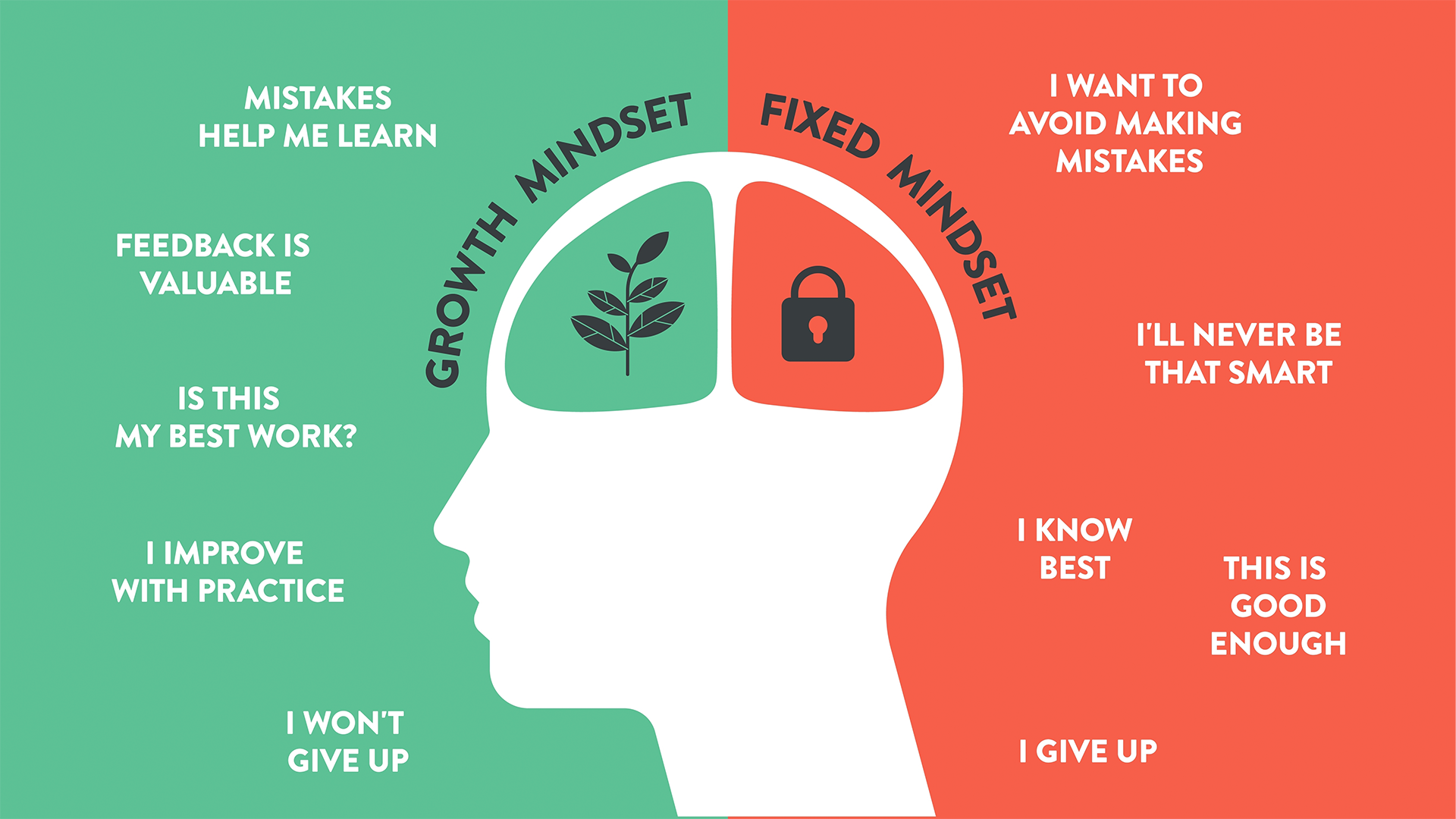

She noticed that two main types of mindset were often adopted by students. A growth mindset and a fixed mindset.

Growth Mindset

A student with a growth mindset will view intelligence, skills, abilities and talents as malleable, things that can be learned and improved through effort. They are typically more persistent and motivated, because they understand that they can improve through work and practice.They are growth-oriented as opposed to results oriented.

The self-esteem of a student with a growth mindset is not attached to any one skill or talent, so they are typically more resilient when receiving a setback through a poor test result and see it as a chance to learn and improve.

Fixed Mindset

In contrast to a student with a growth mindset, a student with a fixed mindset believes that their skills, abilities and talents are relatively fixed. They are typically less resilient to negative test scores as they view it as not being good enough.

These students are often the ones who like to portray themselves as not having to put much work in to achieve high scores as they are naturally smart, or 'gifted'. They are less likely to embrace the process of learning and growing, and rather see them as threats to their self-esteem.

Students with a fixed mindset are more binary in their thinking; “I’m either good at something or I’m not”, and get frustrated when they can’t do something.

Common traits of a growth versus a fixed mindset.

Due to the nature of these two contrasting mindsets, students with a growth mindset are more likely to seek out feedback and use it to improve their performance. They are likely to be more receptive to coaching.

It can be a real challenge for an academic coach to install a growth mindset into a student with a strongly fixed mindset; particularly if the student is performing well and has a talent for the subject, as what they are doing appears to be working.

Nevertheless, it’s incredibly important to do so, because at some stage it will hold them back and stop them from achieving their full potential.

Yes, they might get through their GCSEs without any issues, but at some point everyone (even the highest performers in the world) need to adopt a growth mindset to continue to improve and see failures as an opportunity for growth.

Coaching students with ADHD

In addition to all of the other areas discussed above, there is another important variable which needs to be considered as an academic coach.

Additional learning difficulties can arise from students with ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia and dyscalculia that will often require a more specific and specialised form of coaching.

We asked an expert tutor and top Bramble user, Alexandra Van-Gelder, who specialises in coaching students with ADHD, to share some tips on effective methods for these students.

It’s not uncommon for students with ADHD to often be viewed as gifted children, though as they age they appear to lose focus. In fact, some gifted characteristics can overlap those associated with inattention and hyperactivity as the student may not be getting enough stimulation in the classroom which increases their propensity to become distracted.

Alexandra suggests that many of the coaching methods that work for most students often don’t work for students with ADHD.

For example, a common revision method is to revise for 45 minutes, followed by a 15 minute break. However, students with ADHD generally have more difficulty starting, as well as stopping a task. So in this situation starting and stopping revision less often is actually beneficial to the student.

It’s therefore particularly important for the coach to foster a growth mindset (see above for details) in students with ADHD.

A coach should be reassuring that it’s okay for them to make mistakes as it’s part of their individual growth and development. If the student is undiagnosed and the coach suspects they might have ADHD, it is advisable to speak with the parents about getting tested.

If the student with ADHD is also ‘gifted’, they may find that it’s easier than most to pick up and retain information, which can obviously be beneficial in an academic setting. However, they might also have slower development of executive functioning and require more assistance with tasks such as planning, organisation, self-management and completing tasks on time.

On the other hand, some students with ADHD might struggle with memory and recall.

If this is the case, using specific memory-based techniques, such as mnemonics and memory palace, is advisable.

As a final point, a student with ADHD might have a little more trouble in their social environment, picking up on social cues and appearing to lack interest in non-reciprocating interests and ‘small talk’. Obviously, this could have a knock on effect with their academic life if they are not in an environment with like-minded individuals or people who will resonate with them.

This is where a coach can assist as a confidant and as someone who understands their needs.

Like all students, those with ADHD will all be different and the approach it takes with two students will vary.

Here are some general tips:

- Choose an optimal study environment. For some this could be with some background or ‘white’ noise. For others it might need to be devoid of anything that is likely to cause distraction.

- Use a wide range of resources. Keep the brain stimulated. Students with ADHD will generally respond well to novelty and variety.

- Use breaks wisely. If the student struggles with stopping and starting revision, it might be best to have fewer breaks and longer periods of revision. However, the opposite might also be true for some students.

- Empower the student with independence. Students will respond better to questions, options and making their own choices and decisions, rather than simply being told what to do and when.

- Facilitate a level of self-advocacy in the student. Highlight and ultilise areas where they have natural strengths and affinities and assist them with tasks they find more challenging.

Technology and academic coaching

The role of technology in academic coaching cannot be overstated.

As technology and Artificial Intelligence (AI) continues to progress and increasingly work alongside humans, it is becoming more important than ever for subject tutors to become academic coaches.

Given the volume of high-quality resources now available online, it’s only a matter of time before AI can deliver content material to students in increasingly effective and efficient ways.

Think about it. Does it make sense to deliver the same subject material (i.e. a taught lesson on the cell cycle) over and over? Is that the best use of your valuable time with the student?

This is where technology can take an important role in content delivery for tasks which are less personalised and more repetitive.

This process has already started with the use of video tutorials, flipped learning methods and other forms of online learning.

However, AI is set to take content delivery to the next level.

So what does this mean for tutors?

They must be able to coach students effectively. Based on individual needs.

Yes, subject expertise will still be important for the feedback and questioning loop. However, technology and AI will not be able to assist students with the highly personalised aspects of coaching discussed in this article. That’s where the true value of an elite tutor and academic coach will shine.

Students require coaching to learn how to learn in the most efficient and effective ways for them. This is non-generic, specific and individualised. Content delivery itself is far less specific, as it contains set material. The only variable is the method by which it is delivered and the resources used to illustrate a concept.

Using technology platforms well-suited to academic coaching is also an important consideration.

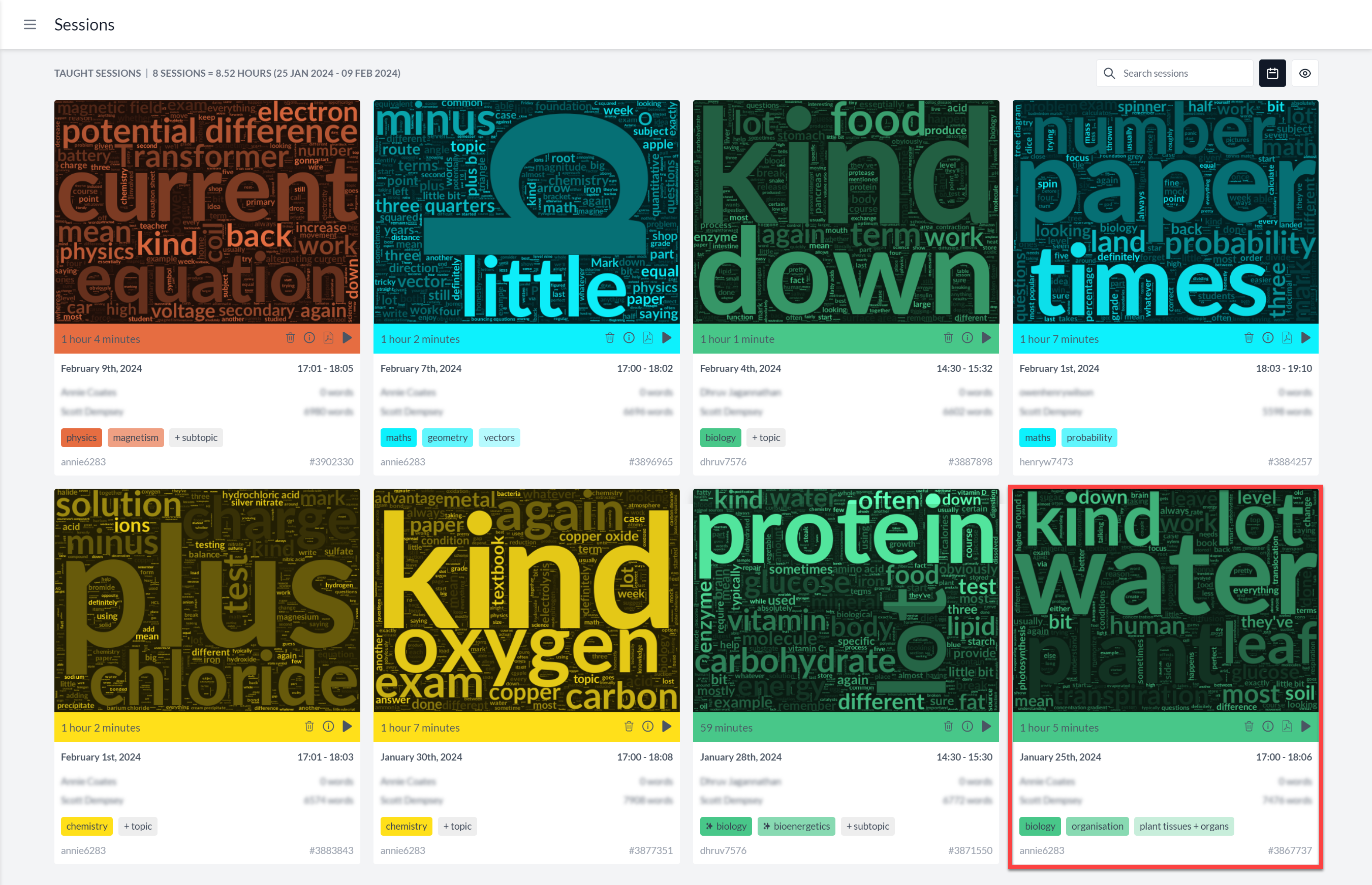

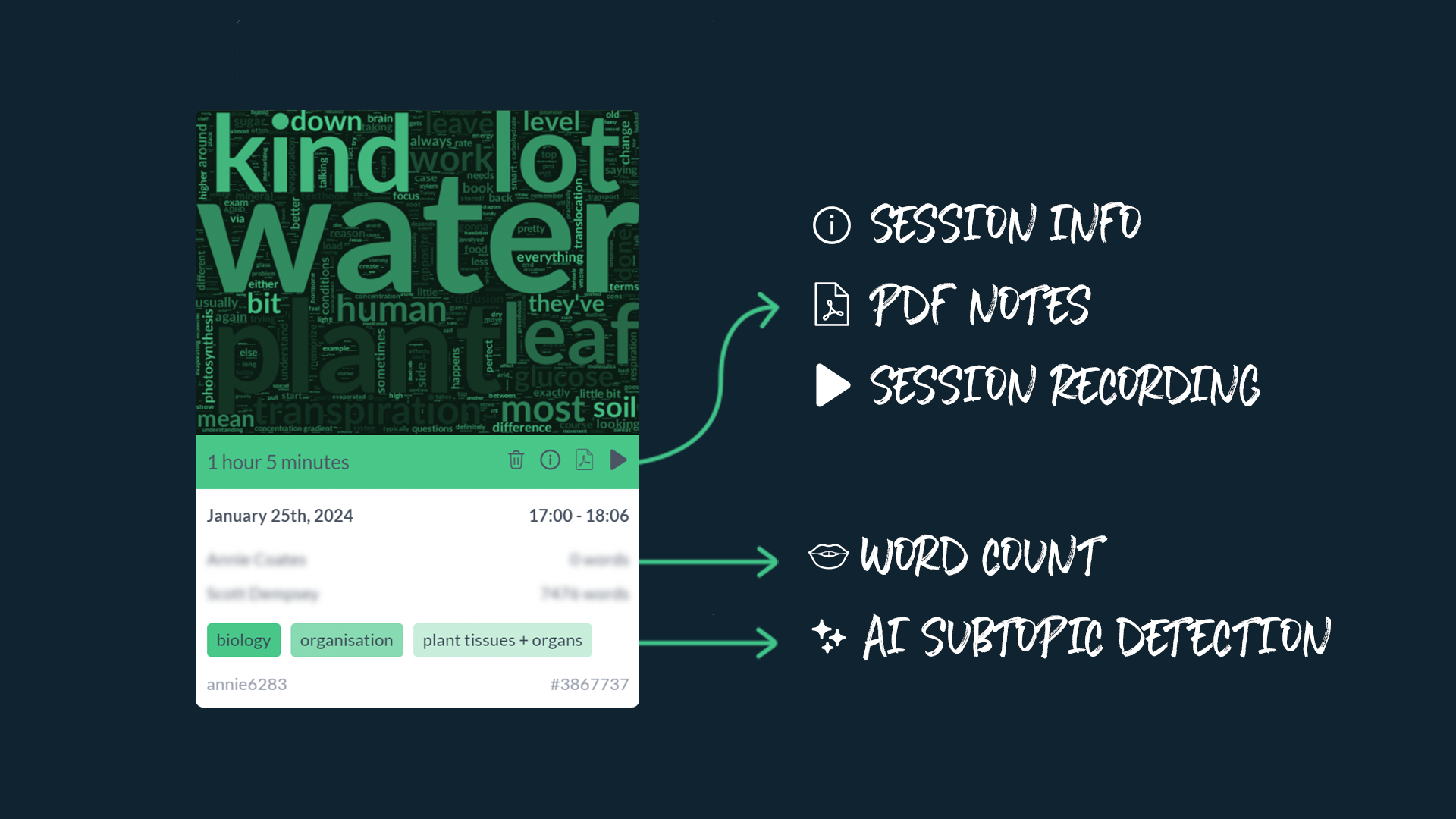

The captured content and session playback features in Bramble provide a crucial part of reviewing lesson performance and progress.

The captured content and playback features in Bramble make session analysis simple, fast and effective.

It wasn’t long ago when coaches from other industries had to capture their sessions on video recorders in order to review and analyse them. Now we have session libraries that automatically capture everything ready for review immediately.

Additional data shown on session synopses is also incredibly valuable.

Engagement metrics such as words spoken, strokes drawn, and resources uploaded give an immediate representation of how engaged the student was during the session.

Feedback and review systems such as CUE Ratings are also a valuable tool for documenting and analysing student performance over time. Too often students cannot see the progress they are making outside of school examinations. So providing them with weekly feedback enables them to remain motivated and quickly spot when they get off track.

To conclude, humans and technology are progressively working in a synergistic fashion to provide better and more effective solutions across industries, and while the education industry is often a little behind the curve in this respect, it’s exciting to see how the role of online learning and tutoring changes over time.

My guess is that it will progressively require tutors to become academic coaches as the role of technology in content delivery becomes more influential and impactful.

To work with Scott, or for more information on coaching and technology in education, contact scott@bramble.io.

To work with Alexandra, or for more information on coaching and tuition with ADHD, contact alexvangelder10@gmail.com.